Thursday, December 23, 2010

I'm coming back...

Sunday, August 1, 2010

Good Interns

-The reputation you make for yourself on day 1 will last for the remainder of your residency. Be nice, keep your head and don't blow up at nurses. I'm sure you've heard it before, but nurses can make or break you. You never know who knows who in the hospital, so make sure you mind your p's and q's.

-Write everything down. When someone asks you to do something, put it on your list.

-Make check boxes and cross stuff off the list as you go.

-Do things as they come up, if you can. If you can't, you have to prioritize.

-Check and recheck things throughout the day. Follow-up on lab results and tests and keep people up to date.

-Get patients out of the hospital. You're job is to help move patients out, otherwise, they will just linger forever. Make it your mission. Remember, bad things happen to people in hospitals.

-Don't leave the task at hand, unless someone's about to die. Walk, don't run to codes. You need to make sure you have collected your thoughts before you walk into a chaotic room. You're supposed to be the one who knows what to do. Start with A and go in order. Make sure a senior person knows the situation.

-When you get a call about a patient, go see the patient, especially at the beginning. Towards the end, you'll be able to triage more effectively over the phone.

-Call for help. Your more senior residents have been there before. If you figure stuff out on your own, and no one ever gets hurt, that's great, but if you mess something up and someone dies, and you didn't ask for help, you'll never live that down.

-The most important thing that a surgical intern can do is keep the operating room going. Call the consultants, go to the Echo reading room yourself, do whatever you have to do to get the patient into the operating room safely.

-Stay until your work is done. You might find that you are staying late at the beginning, but you'll become more efficient with time. None the less, your more senior colleagues will appreciate your willingness to be a team player.

-Read as much as you can.

-Do something besides work. Otherwise, you'll go crazy.

Monday, May 17, 2010

Nothing to say...

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

The Empty Operating Room

At the end of the day today, I was walking through the OR hallway. Most of the cases had ended for the day, the rooms were empty and had been setup for tomorrow's cases. I couldn't help but walk into a room and sit down for a minute, to dream about my opportunity to perform for the crowd. It's hard to dream about the end of the game before the national anthem has even been played, but it's important to have practiced that game winning free throw before the score is tied with 1 second left and you're at the line to win the game.

OK, I'm done with the ridiculous sports analogies. I was just stuck in the moment on my way through the OR and thought I would share.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

Taking the scalpel...

It's pretty scary, taking a piece of sharp steel to a person's skin. Although I feel like I have a good understanding of anatomy, it's never enough to have just looked in Netter's before going to the operating room. I'm not the most spatial person in the world, but boy is it important to learn human anatomy in layers. A couple of days ago, I had a nightmare that I cut a patient's superficial peroneal nerve in an approach to a fibula fracture. I can't imagine having to go and tell a patient's family that I messed up their loved one. Hopefully, I won't ever have to figure out how it's done.

Getting permission to cut through a person's skin and mess around with their insides is a big deal. I think that is not necessarily obvious until you are the one holding the knife...

Saturday, March 27, 2010

I Chose the Right Field

There are many people that I have taken care of over the last six months whom I will remember for the rest of my career. Not to mention, many lessons that I will keep with me. In addition to the patients, off service rotations are important because they give you an insight into how other services operate. You get an opportunity to meet the residents and attendings on other services and develop an understanding of what is and what is not an appropriate reason to request consultation. I also enjoy getting into the operating room with other surgeons. There, I have been able to pick up a variety of important surgical techniques that will make me a better surgeon.

Sunday, March 21, 2010

Own the Bone: Osteoporosis and the Orthopaedic Surgeron

Osteoporosis is the result of an imbalance in bone metabolism. In the physiologic system, bone is constantly being broken down and repaired by a very tightly controlled interplay between osteoblasts (bone forming cells) and osteoclasts (bone resorbing cells). This interplay is modulated by a variety of hormones including parathyroid hormone, calcitonin, Vitamin D, estrogen and testosterone, just to name the most important.

There are two types of osteoporosis: primary and secondary osteoporosis. Primary osteoporosis is the most common and is related to menopause (or loss of estrogen) or extremes of age (also known as senile osteoporosis). Secondary osteoporosis is the result of a disease process such as multiple myeloma or endocrine imbalance. Secondary osteoporosis can also be caused by exogenous corticosteroid use, even at doses as low as 10mg daily, although some may not argue this is not a necessarily low dose of prednisone.

Because of the morbidity and mortality of osteoporosis related fractures, not to mention the cost of care, appropriate individuals should be screened for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. This includes all women over 60 years of age, men over seventy, and individuals over 50 at increased risk for osteoporosis: those with previous fragility fracture, family history of fractures, frailty, low BMI, and treatment with medications such as corticosteroids, anticonvulsants, long-term heparin use, chemotherapeutic/transplant drugs, hormone/endocrine therapies, lithium and aromatase inhibitors. Of course, all individuals presenting with suspected fragility fractures should also be screened for osteoporosis, either in the acute setting or as an outpatient soon after their discharge from the hospital.

Screening is achieved through a variety of modalities, most common being dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). This radiographic test is used to asses bone density in the hip and spine. This density is then assigned a t-score and a z-score. The t-score is a comparison to the bone density of healthy young adults. The z-score is a comparison to age and sex matched individuals. Most commonly, the t-score is used to make a diagnosis of osteoporosis. A t-score greater than -2.5 standard deviations (SD) from the mean is considered to be significant enough to make the diagnosis of osteoporosis. T-scores from -2.5 to -1.5 SD are considered to be diagnostic for osteopenia.

Individuals who present with fragility fractures should have a laboratory work-up to rule out secondary causes of osteoporosis. These studies include CBC with differential, complete metabolic profile including alkaline phosphatase, TSH, and Vitamin D levels. Other studies to consider include serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), 24-hour urinary calcium, parathyroid hormone, testosterone (in males), and many others.

In addition to treatment of the fracture, individuals found to have osteoporosis should be undergo treatment to prevent further bone loss and, in the ideal world, promote a more physiologic bone remodeling to occur. Those who smoke or drink alcohol excessively should be counseled to stop. Post-menopausal women should receive between 1200-1500mg of calcium daily. Adults greater than 50 years of age should receive 800-1000 IU of vitamin D3 daily. Individuals with osteoporosis should be encouraged to exercise and should undergo evaluation for fall risk. This often includes a visit to the home and scrutiny of medication lists for medications which may increase risk of fall. Lastly, medications intended to alter the course of the disease process such as bisphosphanates and estrogen therapy, among other, should be prescribed. This will often entail consultation with a primary care physician or endocrinologist.

As i mentioned in the title of this post, the American Orthopaedic Association has started a campaign that they call Own the Bone. This initiative was designed to increase awareness and encourage orthopaedic surgeons to take a more active role in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. Of course, the management of osteoporosis requires a multi-disciplinary approach, but the catalyst, unfortunately, for treatment is often the first diagnosis of a fragility fracture. One observational study published in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS) by Dell et al. outlined a process by which a group in the Kaiser system was able to decrease their incidence of hip fractures by 38% (970 fractures) using a multi-disciplinary screening approach. If the cost of treating one fracture is estimated at $30,000, that amounts to a total savings of over $29million.

Next time you see a patient with a hip fracture, think beyond three screws versus intrameduallary nail. Start the process to rule out osteoporosis. Consult medicine colleagues to assist in the diagnosis and management of the disease. When seeing patients in the office for non-fracture care, identify and encourage screening in appropriate individuals. This is a way we can have a significant impact on the life expectancy and quality of life of our patients.

Sources

Dell et al. "Osteoporosis Disease Management: What Every Orthopaedic Surgeon Should Know." JBJS.

2009;91 Suppl 6:79-86.

Jacobs-Kosman et al. "Osteoporosis." Emedicine: Rheumatology.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/330598-overview

Lucas and Einhorn. "Osteoporosis: The Role of the Orthopaedist." JAAOS. 1993;1:48-56.

Saturday, March 20, 2010

The End of Intern Year

With that, congrats to all who matched. I'm looking forward to your arrival.

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

The Value of Communication

Nec fasc is shorthand for necrotizing fasciitis, more commonly known as flesh eating bacteria. This is not a diagnosis that should be taken lightly, nor should it wait 30 minutes to be seen! If the patient really has necrotizing fasciitis, and you leave them for another 30 minutes, they could lose a limb, or worse, their life. Compartment syndrome is the same sort of situation. These are examples of orthopaedic emergencies, situations when a consultant should drop what they are doing and go see the patient immediately. Granted, the yield for these consults is somewhat low, but if you're concerned enough to worry about something that is considered an emergency, you should call and talk to the person who will be doing the consult directly. Imagine if I placed a computer consult to the cardiologist that said 'rule out ST elevation MI,' and then allowed the patient to lay in their bed for the next 20-30 minutes waiting for the ward secretary to notice the order on the printer and call the consult!

It's not just emergent consults, however. If another service wants me to come and see a patient, I'm always happy to. I'll never refuse a consult. I do, however, appreciate a phone call to hear the story first hand. Not only do I like to hear the story, it's always easier to understand the question when you can ask questions back. If imaging needs to be ordered, I can make sure I have everything I need to take appropriate care of the patient.

Communication, however, is a two way street. Common sense would say that when you are finished with a consult, you should call the consulting service and discuss your recommendations. Sure, the recommendations are scribbled on the chart or dictated and won't be available to read for another 6-8 hours. Calling gives the consultant the ability to explain their plan and the thought process behind that plan. It provides an opportunity for the person who placed the consult to ask questions. Most importantly, it makes sure everyone is on the same page.

Too many times, especially in a large medical center, the plan gets confused. One hand doesn't know what the other is doing. Each individual team is making recommendations that contradict the other. In the end, the patient and their family becomes confused and frustrated, and that is a recipe for disaster.

Friday, March 12, 2010

Ring Enhancing Lesions

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

Syndrome Unrealistic Expectations (SUE)

This is an incredibly prevalent disease. Not only is it seen among patients in both the inpatient and outpatient setting, but also in their family and friends. Some common symptoms include improper utilization of medical resources, delusions that health care is free and labile mood. There are associations with chronic pain syndromes, tobacco abuse and a never ending request for the drug 'dilauda.' The disease is seen in both men and women and in people of all races. No diagnostic tests are usually necessary or available. It is strictly a clinical diagnosis.

There is no known cure for this disease. It seems to be communicable and maybe even heritable. Groups are working on developing a vaccine and are enrolling interested individuals in studies.

Monday, March 1, 2010

Strength in Numbers

Whitecoat makes an interesting suggestion on his blog: that physicians should just allow the cuts to take effect, but then stop taking care of Medicare patients. His argument is simply that instead of allowing our healthcare system to continue to teeter on brink of death, why not just allow the natural history of the disease to progress and force the collapse of our healthcare system that will in turn, push us more towards the overhaul that we so desperatly need.

One group of physicians at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona has done just that. That have stopped seeing Medicare patients. There are, of course, two sides to this argument. First, and foremost, how would such an approach in large numbers affect care for those who qualify for Medicare? Second, is it fair for physicians to accept a 21% pay cut in return for taking care of often very complex medical problems? Let's not forget that the current level of reimbursement is hardly adequate.

I have another suggestion, and it's a crazy one. What would happen if all of the physicians in a certain specialty in a certain area decided to form what would in essence be one large practice? What if all of the orthopaedic surgeons in one state decided that they were going to join together and refuse to take care of Medicare patients?

We're going to get to a point where crazy things have to happen. We've seen what Congress has been able to do with health care reform. For the send time in 20 years, they have attempted to make a change, and their attempt failed. The jury is still out on what can be done, as President Obama is pushing hard for meaningful reform to occur. I've said it before, and I'll say it again, we're asking the wrong people to enact the change.

It's time for physicians to take charge of their own destiny. While many of us would rather not get in the mix and just stick to the business of taking care of our patients, this approach is nearly as ineffective as my crazy idea above. We're not doing our patients any favors by allowing this current strategy of using temporary patches to stave off the inevitable.

Sunday, February 28, 2010

Look at the Pictures Please

Reading the report to me is worthless. Waiting all of that time before calling is a huge waste of time. If you push on a bone and it hurts, go look at the x-ray. Look at the picture where it hurts. If you see a fracture, give me a call and I'll come and take care of the patient. If you push on the bone and it hurts but there isn't a fracture, it is still OK to call. For one, I don't depend on the report to make my diagnosis. I, like most of my colleagues, will read the films myself. The radiologist's read is more of a quality control issue to make sure I'm not missing something. Additionally, maybe the patient needs another study, or in the case of snuff box tenderness in the wrist, perhaps we'll just go ahead and splint them and treat them like they have a fracture.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Entiltement

This, in itself, is not an uncommon occurrence. On occasion, I will make a mistake with a prescription, or forget to include a home medication that the patient asked to have refilled. In this instance, however, the patient and family wanted to talk to me because the hospital's prescription assistance program would only agree to fill part of one of the narcotic scripts that I had written.

This complaint, alone, isn't really that big of a deal. I have a lot of conversations with patients about their ability to pay for medications. When I write a prescription for anti-nausea medication, I write for both Zofran and Phenergan because although I prefer to give my patients Zofran, it is expensive and some insurance programs will not pay for it. If I know that the patient is self-pay, I explain the difference in cost, give them both prescriptions and let them decide which they can afford. Oxycontin, as another example, is quite expensive. It can be up to $5 per pill.

The discharge planner explained to me that the hospital had limits on what it would provide for different medications, based on cost. Not only that, the discharge planner explained that although the patient had a job (but no insurance), she didn't feel like she would be able to pay for her stay. Because of this, the hospital had agreed to pay for her stay and all of the care that she had received. When you add it all up, the bill is probably way more than $100,000. When the discharge planner asked the patient how much of their care they would be able to pay for, the answer was NONE! The patient and their family expected that all of the care would be provided by the hospital, and had no intention of paying anything.

When I went to talk to the family about the limitations of the program, they couldn't understand the hospital's position. I was left with explaining that all I could do was write two prescriptions, one for the hospital's program, and the other for the patient to fill at a retail pharmacy, which they would have to pay for. They were still somewhat upset when I left the room.

This is not an isolated incident. I have heard many comments from patients stating that they didn't intend to pay for their care. When cost is brought into a conversation about prescriptions or length of hospital stay, patients will often mention that they have a medicare card or no insurance and they will not be paying their bill.

Imagine, for a second, if I went to the nicest steak house in town to order the most expensive cut of meat and the oldest bottle of wine on the menu. Let's say I asked the waiter the cost of these items, and then after his response, commented that it didn't matter because I didn't intend to pay anyway. Do you think I would get served that steak and wine? I doubt it. In fact, I would probably be asked to leave, or even more unthinkable, to pay for my meal ahead of time. If I told that story to 100 people, not one person would find that response by the restaurant to be unreasonable. If, instead, I substituted the story above about the Oxycontin, I don't think the response would be so predictable.

What do we have to do to get across to our patients that they have a responsibility to participate in (pay for) their care? This includes paying for the services of the hospital and its staff. Is the cost of care in our country over inflated? I believe that it is. Should we charge our patients $20 for a Tylenol? Absolutely not! The answer to this problem, is not providing universal coverage to all at the cost of $0. If we expect to reform healthcare and provide coverage to everyone at a reasonable cost, I believe that we have to start from scratch.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

Distal Radius Fracture

When evaluating injury to the distal radius, a complete physical exam and evaluation of neurovascular status should be completed. PA and lateral radiographs should be obtained. The wrist and elbow should be imaged. In assesing the distal radius, several radiographic parameters are important. The first is the radial height, which should be approximately 11mm. Volar tilt should be approximately 11 degrees. Lastly, radial inclination should measure approximately 22 degrees.

There are a variety of classification systems for distal radius fractures. Most commonly, when called from the ED, the consulting physician will describe the injury or use an eponym.

Colles (top left) - This is the most common fracture pattern, with over 90% of distal radius fractures having a dorsal angulation. These can range from simple non-displaced fractures to intra-articular fractures with disruption of the distal radial-ulnar joint (DRUJ). This is the fracture pattern seen after FOOSH injury.

Smith (top right) - In this pattern of injury, the angulation is volar. This injury occurs when the fall occurs onto a flexed wrist.

Barton (bottom left) - Fracture of the dital radius and dislocation of the radial-carpus articulation.

Chaffeur (bottom right) - Fracture of the radial styloid process. These injuries are sometimes associated with disruptions of the carpal bone articulations.

Displaced fractures should undergo closed reduction in the emergency department. A hematoma block and some IV narcotics can provide adequate anesthesia for the reduction.

Reduction of a Colles Fracture

-Hang the wrist with 5-10 pounds of weight at the elbow for 10-15 minutes. The allows ligamentotaxis to assit in the reduction and to bring the fracture out to length.

-Extend the wrist while providing logitudinal traction.

-Use a thumb on the dorsal fragment to push and then flex the wrist to reverse the dorsal deformity of the fracture.

-The wrist should then be placed in a well-molded sugar-tong splint. The wrist should be splinted at neutral. Avoid over extension or flexion as this may place extra tension on the median nerve.

-Post-reduction radiographs should be obtained to confirm adequate reduction.

-Neurovascular exam should be completed.

Non-displaced, minimally displaced, and stable fracture patterns can be treated non-operatively in a cast. Unstable fractures and those that cannot be adequately reduced require operative fixation. Options include percutaneous pinning, use of an external fixator or open reduction and internal fixation with either a dorsal or volar plate depending on the fracture pattern.

**As usual, information for this post taken from The Handbook of Fractures, 3rd ed. Images have been borrowed from Dr. Google.

Saturday, February 6, 2010

Nice Patients/Families Make My Day

I started with showing the pictures and explaining each injury and our treatment plan for that injury. I answered all of their questions and then we spent a few minutes talking about the surrounding area. I made some suggestions about where the family could have some dinner and then went back to my work.

Everyone in the room was nice; smiling and laughing during our conversation. No one complained about the hospital or griped that their family member wasn't in a private room. When I told them to have the nurse page me if they had any other questions, or needed anything that I could help with, everyone said thanks.

Although most of the interactions that I have with patients are not unpleasant, not many are as pleasant as this particular encounter. Maybe I'm not good enough at lightening the mood? I don't know. I do know, however, that something as simple as a good (or bad) conversation with a patient can have a significant effect on the day.

Thursday, February 4, 2010

Lost in the Job

As an intern on a busy surgical service, spending a lot of time with our patients is impossible. On the busiest of days, seeing patients at all can be a struggle. Patients look forward to the time when their doctor(s) visit. They have questions and concerns that they want to address, and they are looking for someone to take some time to explain recent findings and update them on the plan. On top of that, they are "locked up" in an unfamiliar place where bells, whistles and announcements are played all day and night long, people come into their rooms at weird hours to wake them up and ask a million questions and their privacy and dignity are sometimes taken for granted.

Although I don't have an hour to spend with each of the 20 patients on my service every day, I do have a couple of minutes to make some social rounds in the afternoons, to say hello to my patients and make sure their questions are answered and their needs are being addressed. It's not like I don't want to talk to my patients, but more as if I get lost in the workload of being the intern, answering pages and checking and double checking to make sure that everything is being done.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Arranging Your Fourth Year Schedule

This is probably the most control you will have over your schedule throughout your medical school career. Where I went to medical school, we had three months of required rotations and seven months of electives. That leaves two months for vacation. We also had one month of vacation available during the third year, and if you did an elective during that month, you had three vacation months available and were only required to do 6 months of electives.

Let's start with the important part. How might you consider spending your vacation month(s)? First, and foremost, is interview season. Most, if not all interviews take place during December and January. You should plan to be able to travel during both of these months. I did fifteen interviews, six in December and nine in January. You don't necessarily have to use your vacation months as many schools have electives available in their catalogs that do not require an extensive time commitment. There is time for trips if you would like to travel the country/world. Many of my friends have gotten married during their vacation months, so please, do not make it all about business. This is the last year in life that you will get to enjoy, so build in some time for enjoyment.

There is one other matter to consider as you are thinking about scheduling a vacation - board exams. If you are not already aware, you must take two parts of Step 2: the clinical knowledge (CK) examination and the clinical skills (CS) examination. First, you must think about your Step 1 score. Are you happy with that score? Does it make you competetive for Orthopaedics. I would venture to say, if you have a score of 240 or greater, you do not need to worry about taking Step 2 right away. If your score is lower than that, you might want to consider taking the exam earlier in the year. Otherwise, put off the exam for as long as you can. I have been told by many people whom I trust that Step 2 scores are not heavily considered by program directors as long as the Step 1 score meets the cutoff. Which brings us one other important point. Many programs have a cutoff that is programmed into ERAS. If you don't meet that cutoff, they don't ever look at your application. If you think your score might be on the borderline, I would talk to the program director at your school, or the program director of places that pique your interest.

Now, to scheduling.

June - August - Start the year with some orthopaedics, preferably at your home institution. This will allow you to get familiar with what is expected of an ortho sub-i in a relatively safe environment. I've written a post about it in the past, but I'll hit the highlights. Expect to work your tail off. Be helpful but not annoying. Read and prepare yourself for cases. As an alternative, you might want to take one month during this time frame to get involved in a research project. It's not required, but having some research on your CV will prevent you from getting thrown out of a program's interview pile for no good reason. Speaking of CV's, don't forget about ERAS. Make sure you have time to complete your application and run down letters of recommendation. You might be getting these letters during the early part of the year, which is OK - but you should expect to have all of your letters by the end of October, middle of November.

August - October - This is the prime time for away rotations. Pick one or two places that interest you and go visit. If the program allows you to pick which attending(s) you can work with, do some research first and find the program director or chair. Make a point to work with people who can go to bat for you when it's time for the program to make their rank list. Remember, this is a month long job interview, so be on your best behavior at all times. I've seen the match process from the other side now, and I can tell you, it's somewhat difficult to get yourself to the top of the rank list. It is NOT HARD AT ALL to find yourself at the bottom, or off the list completely if you piss someone (even an intern) off. That said, this is probably the best way, if you play your cards right, to get to the top of the list. Programs will rank you higher if you spent time there and did a good job, mostly because all applicants look very similar, and having taken the time to spend a lot of money to work at a place means a lot.

November - Interview offers will start rolling in November 2nd or 3rd. Use this month to do something fun or something required and get organized for your upcoming interviews.

December - January - Keep it light, if you do any rotations at all. You'll be traveling all over during these two months trying to get a job.

February - June - Finish up your required rotations. Spend time with your family and friends. Travel the world. Drink a lot. Do whatever you want because come July, you are a career (wo)man, and you just won't have as much time for that kind of stuff any longer.

July - Time to start learning your trade. Hopefully, you've matched at your #1 program and you are ready to rock and roll.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

I hate Lauge-Hansen

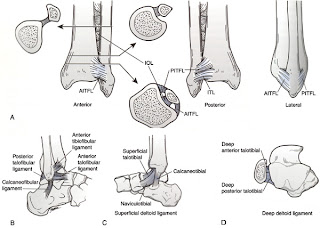

To begin, let's take a quick look at the anatomy of the ankle joint (picture below). The ankle is made up of articulations between the tibia, fibula and talus. The joint is maintained by a variety of ligaments. On the lateral side, the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament and the inferior transverse ligament help to prevent eversion of the ankle. The lateral collateral ligaments of the ankle (anterior/posterior tibilfibular ligaments, calcaneofibular ligaments) help to prevent inversion and anterior translation of the fibula. Medially, the strong deltoid ligament, which has a short and thick deep layer covered by a more superficial layer help to resist inversion of the foot.

Friday, January 29, 2010

Breaking Bad News - Real World Style

Monday, January 11, 2010

The 4AM Page

4AM - working on my couple hours of sleep before rounds - pager goes off...

"Doctor, Mr. So and So's Labs are back"

Na=140

K=4.0

Cr=1.1

BUN=22

Me (To myself) = What the hell is going on? Is this a dream? Is this nurse reading lab values or a textbook? What did I do to piss this person off?

(To Nurse)=Well, those lab values sound excellent. I don't think we'll need to do anything at this point. Thanks for calling...

We even have a replacement protocol to keep that from happening. Not sure if this person was having a bad night or what...I've heard the old adage piss off a nurse and they'll call you for ridiculous stuff.

Sunday, January 3, 2010

H1N1 and Young People

A couple of months ago, I took care of a patient who was admitted to the hospital after elective surgery. He went to the SICU after his surgery (because of the surgery that he underwent, not because he wasn't doing well), was quickly extubated and did great for the first four days.

On post-op day 5, the patient developed a high fever (105 degrees F) and cough. He quickly developed progressive respiratory failure and had to be intubated. Testing confirmed that he had H1N1 influenza.

His chest x-ray looked like the one above. The patient further developed a secondary pneumonia that eventually grew several bacteria, fungi and even another virus.

His chest x-ray looked like the one above. The patient further developed a secondary pneumonia that eventually grew several bacteria, fungi and even another virus.

Eventually, the patient had to be placed on ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) in an attempt to maintain his oxygenation because his lungs were just too sick to provide adequate gas exchange. This patient, unfortunately, did not survive.

In an related story, one of my colleagues took care of a young pregnant lady in the ED who came in with progressive respiratory failure, had to be intubated and went into premature labor. She delivered a still-born fetus and was admitted to the MICU. Imagine seeing an OB, MICU, Pulmonary, Cardiology, Vascular Surgery and ED attending with their respective entourages trying to figure out what to do with this patient.

Above is a graph published by the CDC. The full report can be found here. This report details the number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths attributed to H1N1 between April and mid-November 2009. By far, people younger than 65 are much more affected by this particular virus.

Above is a graph published by the CDC. The full report can be found here. This report details the number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths attributed to H1N1 between April and mid-November 2009. By far, people younger than 65 are much more affected by this particular virus.

It looks like, at least at this point, we have surpassed the second peak of the virus. Some experts, however, expect another peak to occur as we approach what is typically the worst of flu season.

The moral of the story is this: if you have young children, get them vaccinated. If you are <65, you should get yourself vaccinated. That's my PSA for the day.

Saturday, January 2, 2010

What does it take to be an Attending Orthopaedic Surgeon?

I cannot really quantify the beginnings of my education, but you first have to think about 13 years of primary and secondary education followed by an undergraduate degree and preparation to take the MCAT before one can ever enter medical school.

Medical school is where I can really begin to quantify the amount of time spent during my education. For the first two years of school, I was in class or studying for at least 12 hours per day, 6 days per week. Each semester was 16 weeks long, for a total of 64 weeks of school. That equals 4,608 hours of class/studying. In my first two years of medical school, I took approxiately 90 exams, not to mention the rite of passage that is the USMLE Step 1.

Years 3 and 4 are somewhat less vigerous from the standpoint of pure hard-nosed studying. Although I don't know exactly how many weeks we worked per year, I estimated 45 working weeks per year and 50 hours per week of studying/working/wasting time following residents around the hospital. That comes out to be a total of 2,250 hours. As a 3rd/4th year student, I took 6 shelf-style exams and 5 "home grown" clerkship exams, not to mention USMLE Step 2 CS and CK.

The totals for medical school include 104 exams and 6,858 hours studying, in class or "working."

Fast forward to residency. We get 3 weeks of vacation per year in my program, which equals 49 working weeks per year. At 80 hours per week, the total is 19,600 hours, which does not include time preparing for cases or studying for exams. I will be taking USMLE Step 3 in a few months, and will take 5 Orthopaedic In-Training Examinations throughout my 5 years as a resident. At the end of my residency training, I plan to do a fellowship and will have to take at least two exams to become board certified in Orthopaedic Surgery. For the purpose of numbers, let's assume that a fellow will work 49 weeks during their year and will work about 80 hours per week (which could be more/less depending on call, team coverage or research depending on the fellowship). The total there is 3,920 hours.

The grand totals come up to 30,378 hours of education/studying/working and 112 exams, not to mention research activity and some other things that I might have forgotten about. Granted, this is not an exact accounting of hours, but I would say it is pretty close and may even be an underestimate.

I'm not sure why it matters, or even what brought the question to mind, but I thought the numbers were interesting. Deciding to become a physician is not a small commitment, and the amount of training necessary to be theoretically able to cut someone open and put them back together again is extensive.

Friday, January 1, 2010

New Year, New Focus

Over the past six months or so, I have blogged mostly about educational topics. Although I want to continue along that vein, this year, I also want to include some patient interaction experience and hopefully throw out some other topics that spur discussion and maybe even some controversy. We'll see how it goes. Thanks for reading.