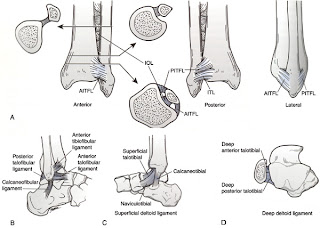

To begin, let's take a quick look at the anatomy of the ankle joint (picture below). The ankle is made up of articulations between the tibia, fibula and talus. The joint is maintained by a variety of ligaments. On the lateral side, the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament and the inferior transverse ligament help to prevent eversion of the ankle. The lateral collateral ligaments of the ankle (anterior/posterior tibilfibular ligaments, calcaneofibular ligaments) help to prevent inversion and anterior translation of the fibula. Medially, the strong deltoid ligament, which has a short and thick deep layer covered by a more superficial layer help to resist inversion of the foot.

When a patient has an complaint of pain/trauma about the ankle, in addition to a complete physical exam, radiographs should be obtained. A standard series includes AP, lateral and mortise views of the ankle. The mortise view is shot with the ankle rotated approximately 15 degrees to be perfectly perpendicular with the transmalleolar axis. When reading ankle films, the medial clear space (distance between the medial articular surface of the medial malleolus and talar dome) should be less than 4mm on the mortise view. In addition, the tibiofibular clear space (distance between the medial wall of the fibula and the tibial incisural surface) on a mortise view should be less than 6mm.

In terms of classification, there are two classification systems. The first is the AO or Weber classification system, which is dependent upon the fibula fracture pattern.

-Type A is a fracture below the level of the syndesmosis. These are usually stable fractures caused by an inversion of the foot.

-Type B is a fracture at the level of the syndesmosis. This is the most common type of ankle fracture. If the medial side of the ankle is not injured, these are often stable injuries. In a patient with a Weber B fracture without an obvious medial malleolar fracture, stress radiographs should be obtained to evaluate the syndesmosis. Stress views are obtained with manual dorsiflexion and external rotation of the ankle.

-Type C is a fracture above the level of the syndesmosis. These fractures usually occur as the result of an external rotation of the ankle. These fractures are often unstable because of associated medial sided injury.

While the Weber classification system is quite simple and easy to understand, the Lauge-Hansen (LH) classification system (images below) is much more commonly used to better understand the mechanism of injury. The classification system is based on the pattern of injury to the ankle. First, the position of the foot is described as either pronated or supinated and then the deforming force of the foot (adduction, abduction, or external rotation) is described as well. Each fracture pattern has additional stages described for a more complete understanding of how additional force leads to progressive deformation and injury to the ankle. As in the Weber system, the LH classification is described primarily based on the fibula fracture pattern.

Treatment of ankle fractures is based on the stability of the fracture pattern. In general, fibula fractures without associated disruption of the medial deltoid ligament are considered to be stable injuries that can be treated non-operatively in a boot or short leg cast. If the medial structures are compromised, surgical treatment provides much more desirable outcomes. While the fibula is often fixed with a plate and screws, cannulated screws are often all that is necessary to provide the necessary fixation for medial malleolus fractures. In addition to fixation of the fractures, the syndesmosis must be evaluated and stabilized if it is disrupted. This is often achieved by insertion of a screw from the fibula into the tibia. Post-operatively, patients should maintain non-weightbearing status until the fracture has healed. They are often started in a short leg splint which is converted to a walking boot once the patient can begin weight bearing.

Thanks for your thoughts on this subject.

ReplyDeleteI experienced a Type C with rupture and fib fracture near the upper portion of my calf. It's been 3+ months since the "gravitational anomaly".

I'm mostly concern with an almost non-existent dorsiflexion. On a good note: I can finally(while wearing a camwalker) ride the bicycle that once conspired my demise.