Sunday, January 31, 2010

Arranging Your Fourth Year Schedule

This is probably the most control you will have over your schedule throughout your medical school career. Where I went to medical school, we had three months of required rotations and seven months of electives. That leaves two months for vacation. We also had one month of vacation available during the third year, and if you did an elective during that month, you had three vacation months available and were only required to do 6 months of electives.

Let's start with the important part. How might you consider spending your vacation month(s)? First, and foremost, is interview season. Most, if not all interviews take place during December and January. You should plan to be able to travel during both of these months. I did fifteen interviews, six in December and nine in January. You don't necessarily have to use your vacation months as many schools have electives available in their catalogs that do not require an extensive time commitment. There is time for trips if you would like to travel the country/world. Many of my friends have gotten married during their vacation months, so please, do not make it all about business. This is the last year in life that you will get to enjoy, so build in some time for enjoyment.

There is one other matter to consider as you are thinking about scheduling a vacation - board exams. If you are not already aware, you must take two parts of Step 2: the clinical knowledge (CK) examination and the clinical skills (CS) examination. First, you must think about your Step 1 score. Are you happy with that score? Does it make you competetive for Orthopaedics. I would venture to say, if you have a score of 240 or greater, you do not need to worry about taking Step 2 right away. If your score is lower than that, you might want to consider taking the exam earlier in the year. Otherwise, put off the exam for as long as you can. I have been told by many people whom I trust that Step 2 scores are not heavily considered by program directors as long as the Step 1 score meets the cutoff. Which brings us one other important point. Many programs have a cutoff that is programmed into ERAS. If you don't meet that cutoff, they don't ever look at your application. If you think your score might be on the borderline, I would talk to the program director at your school, or the program director of places that pique your interest.

Now, to scheduling.

June - August - Start the year with some orthopaedics, preferably at your home institution. This will allow you to get familiar with what is expected of an ortho sub-i in a relatively safe environment. I've written a post about it in the past, but I'll hit the highlights. Expect to work your tail off. Be helpful but not annoying. Read and prepare yourself for cases. As an alternative, you might want to take one month during this time frame to get involved in a research project. It's not required, but having some research on your CV will prevent you from getting thrown out of a program's interview pile for no good reason. Speaking of CV's, don't forget about ERAS. Make sure you have time to complete your application and run down letters of recommendation. You might be getting these letters during the early part of the year, which is OK - but you should expect to have all of your letters by the end of October, middle of November.

August - October - This is the prime time for away rotations. Pick one or two places that interest you and go visit. If the program allows you to pick which attending(s) you can work with, do some research first and find the program director or chair. Make a point to work with people who can go to bat for you when it's time for the program to make their rank list. Remember, this is a month long job interview, so be on your best behavior at all times. I've seen the match process from the other side now, and I can tell you, it's somewhat difficult to get yourself to the top of the rank list. It is NOT HARD AT ALL to find yourself at the bottom, or off the list completely if you piss someone (even an intern) off. That said, this is probably the best way, if you play your cards right, to get to the top of the list. Programs will rank you higher if you spent time there and did a good job, mostly because all applicants look very similar, and having taken the time to spend a lot of money to work at a place means a lot.

November - Interview offers will start rolling in November 2nd or 3rd. Use this month to do something fun or something required and get organized for your upcoming interviews.

December - January - Keep it light, if you do any rotations at all. You'll be traveling all over during these two months trying to get a job.

February - June - Finish up your required rotations. Spend time with your family and friends. Travel the world. Drink a lot. Do whatever you want because come July, you are a career (wo)man, and you just won't have as much time for that kind of stuff any longer.

July - Time to start learning your trade. Hopefully, you've matched at your #1 program and you are ready to rock and roll.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

I hate Lauge-Hansen

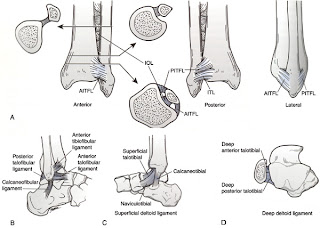

To begin, let's take a quick look at the anatomy of the ankle joint (picture below). The ankle is made up of articulations between the tibia, fibula and talus. The joint is maintained by a variety of ligaments. On the lateral side, the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament and the inferior transverse ligament help to prevent eversion of the ankle. The lateral collateral ligaments of the ankle (anterior/posterior tibilfibular ligaments, calcaneofibular ligaments) help to prevent inversion and anterior translation of the fibula. Medially, the strong deltoid ligament, which has a short and thick deep layer covered by a more superficial layer help to resist inversion of the foot.

Friday, January 29, 2010

Breaking Bad News - Real World Style

Monday, January 11, 2010

The 4AM Page

4AM - working on my couple hours of sleep before rounds - pager goes off...

"Doctor, Mr. So and So's Labs are back"

Na=140

K=4.0

Cr=1.1

BUN=22

Me (To myself) = What the hell is going on? Is this a dream? Is this nurse reading lab values or a textbook? What did I do to piss this person off?

(To Nurse)=Well, those lab values sound excellent. I don't think we'll need to do anything at this point. Thanks for calling...

We even have a replacement protocol to keep that from happening. Not sure if this person was having a bad night or what...I've heard the old adage piss off a nurse and they'll call you for ridiculous stuff.

Sunday, January 3, 2010

H1N1 and Young People

A couple of months ago, I took care of a patient who was admitted to the hospital after elective surgery. He went to the SICU after his surgery (because of the surgery that he underwent, not because he wasn't doing well), was quickly extubated and did great for the first four days.

On post-op day 5, the patient developed a high fever (105 degrees F) and cough. He quickly developed progressive respiratory failure and had to be intubated. Testing confirmed that he had H1N1 influenza.

His chest x-ray looked like the one above. The patient further developed a secondary pneumonia that eventually grew several bacteria, fungi and even another virus.

His chest x-ray looked like the one above. The patient further developed a secondary pneumonia that eventually grew several bacteria, fungi and even another virus.

Eventually, the patient had to be placed on ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) in an attempt to maintain his oxygenation because his lungs were just too sick to provide adequate gas exchange. This patient, unfortunately, did not survive.

In an related story, one of my colleagues took care of a young pregnant lady in the ED who came in with progressive respiratory failure, had to be intubated and went into premature labor. She delivered a still-born fetus and was admitted to the MICU. Imagine seeing an OB, MICU, Pulmonary, Cardiology, Vascular Surgery and ED attending with their respective entourages trying to figure out what to do with this patient.

Above is a graph published by the CDC. The full report can be found here. This report details the number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths attributed to H1N1 between April and mid-November 2009. By far, people younger than 65 are much more affected by this particular virus.

Above is a graph published by the CDC. The full report can be found here. This report details the number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths attributed to H1N1 between April and mid-November 2009. By far, people younger than 65 are much more affected by this particular virus.

It looks like, at least at this point, we have surpassed the second peak of the virus. Some experts, however, expect another peak to occur as we approach what is typically the worst of flu season.

The moral of the story is this: if you have young children, get them vaccinated. If you are <65, you should get yourself vaccinated. That's my PSA for the day.

Saturday, January 2, 2010

What does it take to be an Attending Orthopaedic Surgeon?

I cannot really quantify the beginnings of my education, but you first have to think about 13 years of primary and secondary education followed by an undergraduate degree and preparation to take the MCAT before one can ever enter medical school.

Medical school is where I can really begin to quantify the amount of time spent during my education. For the first two years of school, I was in class or studying for at least 12 hours per day, 6 days per week. Each semester was 16 weeks long, for a total of 64 weeks of school. That equals 4,608 hours of class/studying. In my first two years of medical school, I took approxiately 90 exams, not to mention the rite of passage that is the USMLE Step 1.

Years 3 and 4 are somewhat less vigerous from the standpoint of pure hard-nosed studying. Although I don't know exactly how many weeks we worked per year, I estimated 45 working weeks per year and 50 hours per week of studying/working/wasting time following residents around the hospital. That comes out to be a total of 2,250 hours. As a 3rd/4th year student, I took 6 shelf-style exams and 5 "home grown" clerkship exams, not to mention USMLE Step 2 CS and CK.

The totals for medical school include 104 exams and 6,858 hours studying, in class or "working."

Fast forward to residency. We get 3 weeks of vacation per year in my program, which equals 49 working weeks per year. At 80 hours per week, the total is 19,600 hours, which does not include time preparing for cases or studying for exams. I will be taking USMLE Step 3 in a few months, and will take 5 Orthopaedic In-Training Examinations throughout my 5 years as a resident. At the end of my residency training, I plan to do a fellowship and will have to take at least two exams to become board certified in Orthopaedic Surgery. For the purpose of numbers, let's assume that a fellow will work 49 weeks during their year and will work about 80 hours per week (which could be more/less depending on call, team coverage or research depending on the fellowship). The total there is 3,920 hours.

The grand totals come up to 30,378 hours of education/studying/working and 112 exams, not to mention research activity and some other things that I might have forgotten about. Granted, this is not an exact accounting of hours, but I would say it is pretty close and may even be an underestimate.

I'm not sure why it matters, or even what brought the question to mind, but I thought the numbers were interesting. Deciding to become a physician is not a small commitment, and the amount of training necessary to be theoretically able to cut someone open and put them back together again is extensive.

Friday, January 1, 2010

New Year, New Focus

Over the past six months or so, I have blogged mostly about educational topics. Although I want to continue along that vein, this year, I also want to include some patient interaction experience and hopefully throw out some other topics that spur discussion and maybe even some controversy. We'll see how it goes. Thanks for reading.